Neuragame

A video game allows you to drive a sports car. Without having to become a millionaire first.

The game allows you to walk the streets of a city. With or without racing. Strolling. Or running. Without a script.

Video game processors and designers are increasingly able to bring a video game closer to reality. The visuals look more and more like reality. In the details. The laws of physics are increasingly reproduced in the sound of the engine, the suspension, the noise of the floor, the weather conditions.

NVidia's Omniverse reality player. Unwary, some may confuse it with a photo or video

In the case of driving cars or piloting airplanes, there are cockpits for sale that add another layer of approximation to reality. These cockpits recreate ground vibrations. They simulate braking, acceleration and curves with their pistons creating their corresponding forces.

Photo. Cockpit yaw 2 vr

Three-dimensional glasses simulate our vision even better. We can turn our face, as we do in real life. Another dimension of approximation to reality.

What else can we imitate from reality in video games?

Will it be very difficult to reproduce winds, humidity, smells? Commercially it is expensive, but technically it is not difficult to bring more layers of reality. A fan can simulate wind. For example.

What is the limit of imitating reality in video games? A cockpit with all the movements, fans, smell reproducers, humidity?

Even the best cockpit couldn't reproduce a long fall. Just small movements, by pistons.

But there is an alternative that releases more approximations with reality. Or all. Or even more than all.

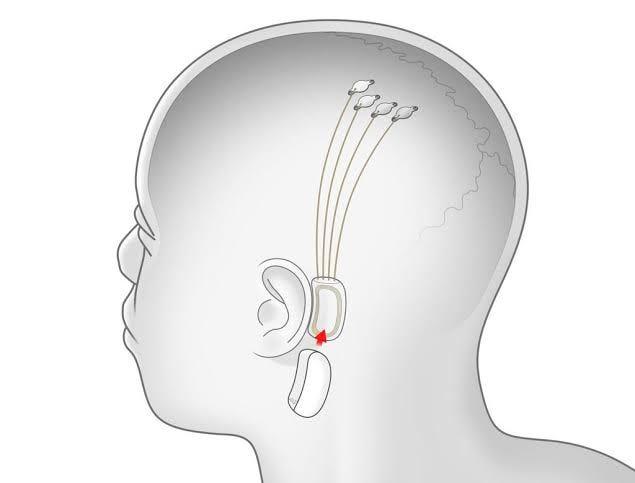

We could connect our mind to the video game.

By connecting our mind to the video game, we wouldn't need any external equipment.

Appropriate impulses could recreate everything we know, without limitation. We could reproduce long falls. Climbs. Any smell. Wind, breeze, smell of flowers — and even new sensations and excitements.

Connected to the brain in two-way, an artificial intelligence — a brain on the outside — could learn, for each player specifically, which impulses result in more pleasure for the player.

In this case, in addition to sending impulses to the brain, the video game could read what the brain feels. Pleasure? Pain? Irritation? Fear? Did our brain respond with a sensation of shivers directed at the spine? A warmth directed at the heart? Did our brain's response lead us to feel a "butterflies in the stomach"?

This avalanche of brain responses is ideal for another brain, only this one on the outside: an artificial intelligence. It's not quite a brain, but a neural network, it is.

A neural network can be programmed to maximize pleasure, for example.

She will.

In this case, as a dedicated employee of pleasure, artificial intelligence will create indexes in its neural network mapping which varied impulses that the game leads to the player gets as a response more, or less, pleasure.

This artificial intelligence — a type of auxiliary brain, on the outside — would begin to guess which impulses cause more pleasure specifically for this player. It could then focus the video game, its scenarios and possible events, on these parts that cause more pleasure for this player specifically.

For example. It is possible that feeling impulses corresponding to large and strong muscles returns signals of pleasure in many people. In certain actions or circumstances.

Can we simulate strength, vigor, or disposition, for our player?

Let's see. Our mind asks to move a leg. Immediately she receives back signals of a large leg muscle moving. This feeling of "large" is what we can artificially amplify, weaken, modify in our simulator.

We can use the player's real desire to move a set of muscles, interfering only with the real response that these muscles return to the player's brain. We can, for example, amplify the feeling of strength and agility of this response.

Several muscles are moved in several interactions per second when we want to make a simple movement. Modern computers can act more than millions of times per second, simulating thousands of muscles at the same time. Therefore, at least theoretically, it is not beyond the reach of computation to simulate real muscle responses, for real brains.

If it is possible to simulate the size and agility of muscles, should we stick to the normal sizes of human muscles?

If it is possible to simulate muscle responses for each muscle command of our player, then we can simulate forces beyond the reach of real muscles. We can have — including feeling — a giant, strong chest, like that of a giant gorilla. We can simulate the agility of a tiger. Or similar.

Sending impulses directly to the brain, in the correct measures and frequencies, allows us to simulate vigor, strength, disposition beyond what working out, eating proteins, even in our most dedicated intentions, allows us to build in real life.

We can simulate both the world and the player's power. We can train a neural network to maximize the scenarios, actions and impulses that bring more pleasure in a personalized way, for each player.

Here we can remember Tom Cruise from the movie Vanilla Sky. He lived in a "video game" designed to give him pleasure. In his video game, Tom Cruise's character dated Penélope Cruz in a humorous romance.

Or we can remember the movie Matrix. In Matrix everything was a big video game.

In both films, defects compel the characters to return to real human life. In Hollywood, returning to real life has been the ending of these types of films.

But here it is put, technically, possibilities of artificial intelligences nurturing us beyond cockpits, televisions and sound boxes. Beyond some movement, vision and hearing.

As we do not usually regress in our discoveries, there may be an ongoing trend, starting, as I said at the beginning, with video games like this small drivable car, today.

What will tomorrow be like?

The next time we observe someone interacting with a cell phone, we can start thinking that using fingers and words on a small screen can evolve, it doesn't stop there.

In Star Trek there was the possibility of going from one place to another instantly. Well, we haven't been able to create the Star Trek tube yet. But we can go from Paris to Tokyo, instantly, in a neuragame. On second thought, what's the difference? By the way: we can even go to Mars. Instantly. Or wherever we want to go. Where would it be?

Responses